When Antonio Brown dramatically the field during the Bucs game vs the Jets, Brady called for empathy, the team implied a mental health issue, and Brown expressed his frustration and mischaracterization. Questioning whether Brown’s mental wellness is fractured to explain deviant behavior is a slippery slope, ripe for misuse by organizations and athletes to rationalize and overlook responsibility for doing more preventative care.

There is a critical distinction separating deviant behavior from mental illness (aka, a clinical disorder). A simple definition for deviant behavior is deliberate actions against well understood norms. There are many different psychological theories explaining deviant behavior. A person can respond to a trigger or stimuli with deviant behavior, and be labelled with a disorder, when, in fact, deviant behavior is not always mental illness. On the other hand, mental illness presupposes deviant behavior. The two labels become interchangeable when we are conditioned early on that there must be an explanation which matches the value system our perceptions developed to makes sense of the world and create a sense of structure. When it comes to mental health, not every behavior has black and white explanation. Consider if I am sitting inside a car and you are observing the car from across the street, we have two different perceptions of the car and the environment. Neither perspective is wrong, except according to the other person. We need to expand our belief system to allow for the “what if” possibility. What if the answer doesn’t come from one of the 4 multiple choice selections we see on assessments? What if there isn’t only one way to fill in the blank on a test? To me, this connects back to Brady’s empathy sentiment. We have a fraction of information, and we may be interpreting this information standing across the street while Brown analysis comes from sitting in the car.

Across industries, to be the best, and to remain the best takes exceptional skill and will. Both are impacted by environmental, social, and biological variables that predispose the expression of behaviors under extreme conditions. How an individual perceives their environment, their role, their place in the hypothetical hierarchy, how they interpret feedback, communication, and the development of coping and adaptation skills are elements combining with past and current relationships (think back to inside the car/across the street analogy) adds critical context. This data helps clarify why Person A doesn’t experience burn out, while Person B struggles with symptoms and influences manifesting either deviant behavior or mental disorder. Given this understanding, organizations have a tangible opportunity to apply and preventatively modify resources as an athlete’s career progresses and endures, to reflect not only physical but mental developmental needs as well.

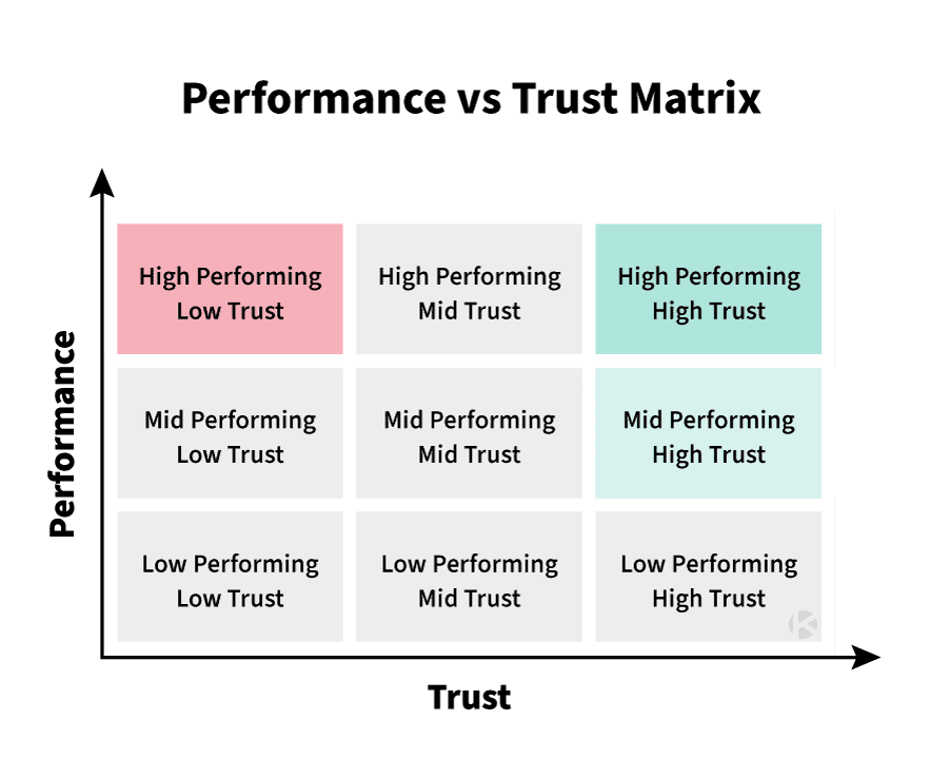

The presence of new external pressure may be the tipping point for some, vs performance pressure. For example, we adapt strength and conditioning loads to account for the accumulating toll of competing, training, injuries, etc over one’s career. Done well, the quality over quantity approach reduces mental drain. However, chances are what’s happening away from competition has increased the mental drain (endorsements, media, personal relationships), especially if the player is one of the best. So how is the entire performance profile being recalibrated to incorporate the past and the present, and reserve will power? First, the individual responsibility is to do the work to evolve and gain self-awareness to harness strengths, apply them intelligently and develop new strengths and new habits sustaining an optimistic and competitive mindset. Doing so builds trust, illustrating to the people around them they can be depended on to perform consistently at or above a high level. To me, this coincides with Simon Sinek’s “Performance Vs Trust Matrix.”

In sports, we have multiple metrics to measure and label someone a high, medium, or low performing. What Sinek’s research with the Navy Seals revealed is the high performing (HP), low trust (LT) individual is not worth the risk proving to be less reliable, unable to execute. Whereas, a MP, HT individual can be counted on to consistently add value and promote productivity. Sports can leverage this analogy and back into trust using the capability quotient (CQ), which is NOT derived from biased observational or gamed self-reporting, or long, culture, race and gender biased assessments. CQ is a derivative of an individual’s written and spoken words. Comparing CQ to current marketplace assessments is like going to the doctor and having your blood work identify and explain the root of the issue contrasted to an assessment/questionnaire being like a patient attempting to explain it a doctor and the doctor (relying on their limited knowledge base and subjective experience) treating a symptom.

(Part 1 of 2)